Despite uncertainty on global financial markets, the UK’s decision to leave the EU and nagging rumours of another recession just around the corner, this year’s TCI Top 100 makes for positive reading. (Click to view full table.)

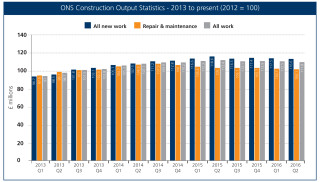

That’s partly a result of timing, of course. The company results used to compile the main table were mostly filed over the past 12 months, which means that they cover the period from the beginning of 2014 through to the end of 2015 – a two-year period when market conditions were at their healthiest since the onset of the economic crash of 2008 (graphically illustrated by the ONS figures shown below).

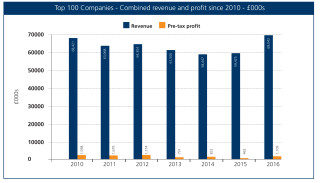

Overall, the numbers appear to be moving steadily in the right direction. Total revenue for the 100 was up by 7.3% to over £69bn, the highest since before the 2008 crash. And profit leapt 53.5% to £1.1bn, though it should be noted that this is well below even the 2012 total. Construction being a notoriously tough industry in which to turn a profit, the average margin nevertheless climbed from 1.1% to a still precarious 1.6%.

But while the headline figures are generally positive, dig a little deeper, and familiar problems emerge.

Revenue was down for 25 of the Top 100, and losses were reported by 19. Some 46 companies either made a loss or saw their profit down on the previous year. And it seems that the old problem of legacy recession contracts is the cause of most of the red ink in the table.

This affects many of the industry’s biggest names. Balfour Beatty’s problems have had the highest profile, with revenue down 4.3% to just under £7bn and losses deepening to £304m from £199m.

Including its latest interims, the firm’s construction services business has lost £840m in the past three and a half years. Group revenue dipped to £8.4bn in its latest annual results for 2015, having hit a peak of over £11bn just four years ago. Half-year revenue for 2016 is down 6%, suggesting this trend will continue.

Laing O’Rourke also ran into headwinds during the past year. Revenue at the UK’s biggest privately owned construction company dropped 12.5% to £3.1bn while profit shrank an alarming 76.1% to £12.4m, and its European business suffered a £58m pre-tax loss.

These financial problems have stemmed partly from problems with Laing O’Rourke’s much-vaunted “design for manufacture and assembly” (DFMA) initiative, which is central to the firm’s construction strategy. The group cited “input cost inflation and delays in delivery using the new construction methods” adding “significant lessons have been learned from these projects”.

The company said it expected “a challenging two years” as it “worked through the portfolio of projects secured in recessionary times, which are being delivered in a period of acute skills shortage and resource cost inflation”.

Group chief executive Anna Stewart stepped down last December, citing ill health, with executive chairman and major shareholder Ray O’Rourke taking over day-to-day running of the business. The firm also put its Australian business up for sale, announced 200 redundancies in the UK earlier this year, and then a wholesale restructuring of the whole Europe Hub operation.

In June, Laing O’Rourke announced plans for a new £100m DFMA plant at Steetley in Derbyshire had been put on hold, pending “a final investment decision”, though it added: “Laing O’Rourke is committed to an advanced manufacturing agenda at the heart of its current and future business strategy”.

The delay, along with the other upheaval at the business in the past year, has raised questions over Laing O’Rourke’s direction. That said, the group’s order book stands at £9.2bn, up from £7.4bn in the previous year, so its pipeline remains strong.

Carillion can be one of the most satisfied of the leading construction players. It took the decision in 2011 to scale back its construction operations, choosing its bids more selectively to protect profit. This strategy has paid off well.

Excluding the Middle East, its construction division turned over almost £1.3bn last year and achieved an operating profit of £37.8m. This gives the business a margin of around 3%, which Carillion expects to be the norm for the coming years, noting that this is “above the industry average” for contracting.

Construction, of course, now accounts for less than half of Carillion’s revenue, with the bulk – over £2.5bn – coming from its facilities management business. This partly explains why Carillion ranks number one by profit in our table, achieving a group-wide return of £155m on turnover of almost £4.6bn.

Interserve, like Carillion, is classified by the stock exchange as a support services provider. Both companies have very similar business profiles, with a substantial Middle East business, and facilities management accounting for the lion’s share of turnover - in Interserve’s case, £2.1bn.

However, unlike Carillion, Interserve’s construction business is another struggling with unsuccessful legacy contracts. Its UK construction operation passed the £1bn turnover mark during 2015, but its operating profit was a negligible £100,000.

The firm blamed the poor performance on “three loss-making energy process contracts within our infrastructure business” which were “due in large part to subcontractor insolvencies and the consequential impacts on project timing and costs”.

One of these, the Glasgow waste-to-energy plant for Viridor, has deteriorated so severely that Interserve has had to set aside provisions of £70m for completion of the contract.

Interserve has since decided to pull out of the waste-to-energy sector, and in a further signal of its antipathy towards construction, has put its equipment business RMD Kwikform up for sale.

But even with its construction problems, the strength of Interserve’s facilities management arm helped the group achieve profit of £79.5m – up 28% on the preceding year – on revenue of £3.2bn. It ranks 7th in the Top 100 on profit.

Mitie is another company that demonstrates the appeal of the support services sector. Turnover shrank slightly to £2.2bn, but profit more than doubled to £96.8m, and it is positioned fourth by profit in the table. Mitie has a fat margin of 4.3%.

But Mitie, like Interserve, had its fingers burnt by the energy sector, taking a hit on a wood- burning power station project in Plymouth. This led the firm to close its M&E business, which made exceptional losses of £15.9m last year.

Mitie is now focusing almost entirely on facilities management, which accounts for almost 90% of revenue. “The FM business provides good, consistent margins and strong organic growth potential, backed by a healthy order book and excellent revenue visibility,” said chief executive Ruby McGregor-Smith.

Kier and Galliford Try both have similar business models, with the construction operations supplemented by housebuilding businesses which bump up the margins at group level.

Both companies have been on the acquisition trail recently, with Kier buying May Gurney and Mouchel, and Galliford purchasing Shepherd’s homes business. The cost of these acquisitions means the two firms have low H-Scores based on Company Watch analysis.

Nevertheless, the acquisitions have helped lift Kier to fourth in the table, with revenue up 10.9% to £3.3bn and profit soaring by 166% to £39.5m.

However, the firm has recently announced that the cost of restructuring to integrate its acquisitions will run to £53m. It hopes to sell Mouchel Consulting to raise cash to plug this black hole. So far, Mouchel’s performance under its new owners has been mixed, with an extra £300m in new and renewed frameworks announced last December, although it forfeited the East Sussex highways contract, lost to Costain/CH2M.

Kier said: “Following the integration of recent acquisitions, simplification of the group’s portfolio is a priority, and will provide focus on the businesses which will underpin the group’s growth expectations in our core markets; infrastructure, building and housing.”

Galliford Try also enjoyed substantial growth, with turnover jumping almost a third to £2.3bn and profit up 19.7% to £114m. The benefit of having a large housebuilding operation in the group is clear; with a 4.9% margin, Galliford is second only to Carillion on profit in the Top 100.

After 11 years at the helm of Galliford Try, Greg Fitzgerald departed as chief executive earlier in the year, handing the reins to Peter Truscott. With forward orders at £3.7bn at the turn of the year, a £500m increase on 12 months before, Galliford Try has a healthy-looking order book.

Truscott said: “Construction continues to enjoy an excellent order book and has grown revenues in the year, with good margins on newer work, although the overall result is still constrained by legacy contracts.”

One of these is the Edinburgh schools project, inherited from its Miller Construction acquisition of 2014, and built under a PPP arrangement in 2005. The schools were shut over the summer due to structural safety fears and Galliford Try has confirmed it has contractual liability for remedial works.

Legacy contracts also caused problems at Morgan Sindall and ISG, tipping both companies into the red last year.

The former posted a loss of £14.8m on increased turnover of nearly £2.4bn. Two defence projects inherited from Morgan Sindall’s acquisition of Amec in 2007 were the chief culprits.

Chief executive John Morgan said the second half of 2015 “saw an improvement in performance as a result of progress made in closing out its older and lower margin construction contracts in London and the south. Looking ahead to 2016, the positive momentum across the group is expected to continue.”

ISG cited “a legacy of poor contracts taken on during the recession” for its £12.9m loss, notably in its now-closed London exclusive residential business. Group revenue was up 12% to £1.6bn.

The fit-out specialist has undergone a “painful restructuring” of its UK construction division, and in February was taken over by Cathexis UK, a US-owned investment fund, and de-listed from the London Stock Exchange. Long-serving chief executive David Lawther was replaced by ISG’s fit-out boss Paul Cossell.

Amey also had a disappointing year. Turnover was up marginally by 2.9% to £2.2bn but profit fell 77.8% to £23.6m.

The company has set aside £55m pending the outcome of a contractual dispute with Birmingham City Council. Amey has a 25-year contract to maintain the second city’s roads and pavements. The dispute resulted in a £41m operating loss for Amey’s local government division.

“Cash collections in the local government sector have proved to be particularly challenging this year, a position which has been exacerbated by the ongoing litigation on the Birmingham contract,” the firm said.

Mel Ewell, chief executive of Amey for the past 15 years, stepped down in February and was succeeded by Andy Milner.

Piling specialist Keller has emerged from difficulties caused by a dispute with main contractor VolkerFitzpatrick on a warehouse contract in Avonmouth to post a positive set of results. Revenue for the year was down marginally by 2.9% to £1.6bn but profit almost doubled to £56.3m.

The geotech specialist, which had set aside a £54m exceptional charge to cover liabilities relating to the groundworks on the Avonmouth scheme, ended up buying the freehold of the building for £62m earlier this year. It hopes this will draw a line under the saga.

Mace has also experienced its share of problem contracts. Revenue climbed more than a fifth to over £1.8bn but profit was up more modestly, by 4.6%, to £36.2m.

Chief executive Mark Reynolds said: “We are now very close to achieving our £2bn revenue target, but are falling behind on margin targets. This is mainly due to legacy projects secured during the recession. Thankfully many now have come to a close and the final ones will be closed out in 2016.”

Skanska is one of the success stories among the industry’s traditional powers. It has managed to increase revenue steadily and remain comfortably in profit – albeit with slightly dwindling margins – throughout the tough recessionary period that has claimed casualties elsewhere in the industry.

Revenue has grown from £1.1bn in 2012 to over £1.4bn in 2015, with profit slipping only slightly from £43.4m to £42.1m in the same period. But against the tough backdrop, that can be considered a pretty decent result. Turnover was up 24% in the first half of 2016.

Mike Putnam, president and CEO of Skanska UK, described the firm’s margin as “sound and stable”.

“Despite a tough contracting environment and with an uncertain future caused by the EU referendum, we have a strong order book and pipeline of work,” he added. “We have also maintained a sound and stable operating margin throughout the first half of 2016. The financial crisis and recession showed that Skanska has a well-honed capability to manage through external change.”

Willmott Dixon, for so long one of the steadiest ships in the industry, saw profits plummet 74.1% to £4.4m even though turnover was up 5.2% to £1.3bn – giving a margin of just 0.4%.

The firm briefly attempted to find a buyer for its support services business, calling off the sale in June.

Group chief executive Rick Willmott said that “continued growth across all our core activities” is rewarding “as we come out of what has been a tough period for our industry”.

Costain, though posting a solid set of results, was not immune to problem contracts.

Turnover was up 17.9% to £1.3bn and profit climbed 15% to £26m. But the one cloud was the Greater Manchester Waste PFI contract, awarded back in 2007, which caused its natural resources division to post a loss of £10.8m.

Chief executive Andrew Wyllie said that Costain had carried out further work on the waste contract during the past year.

“During the course of that further work in 2015, a number of additional issues have been identified and are being addressed,” he said. “The group has incurred further costs and has taken additional provisions to reach final acceptance on the project, which is expected in the second half of 2016, and to complete the remaining works in a time appropriate to the operational running of the plants.”

However, with its infrastructure division raising revenue to £996m, and forward orders rising from £3.5bn to £3.9bn, Costain looks in a strong position.

After Balfour Beatty, the second biggest loss in our table comes from Vinci UK, which was in the red to the tune of £69.4m – which is not such bad news as it represents a substantial improvement on the £216m deficit posted for the previous year. Revenue, however, was also down, at £935.3m compared to just over £1bn the year before.

Chairman Bruno Dupety blames “legacy contracts” for the “poor financial performances in 2014 and 2015”. These are thought to include the delayed Nottingham Tramlink extension. Dupety said the firm’s reduced turnover is due to a more selective approach to bidding, and he predicts a turn of the tide from 2016 onwards.

Vinci has wiped out its debt, but has the second lowest H- Score in our Top 100 of just 9.

Shepherd was another company substantially in the red, posting a £35m loss even though turnover rose to £879.5bn, for an 18-month period to 31st December 2015. Shepherd sold its troubled built environment business to Wates in May 2015 – after big losses in its contracting business – and its housebuilding operation to Galliford Try in September 2015, leaving the group focused largely on its relocatable and prefabrication buildings division, Portakabin.

Sir Robert McAlpine, which six years ago was in our top 10 with over £1.8bn of revenue, has continued a steady slide down the table, now sitting in 25th, and posting a heavy loss of £35.7m on reduced turnover of £805.5m.

The company has experienced several difficult years, and in November 2015 appointed its first non-family member, Tony Aitkenhead, as chief executive. Aitkenhead was the contractor’s project director on the London 2012 Olympic Stadium. However in July 2016, after only eight months as CEO, Aitkenhead left Sir Robert McAlpine having decided that he had achieved everything he had set out to do. The firm said that in this short time at the helm Aitkenhead (who had planned to retire in 2018 in any case) had introduced improvement programmes to transform the business.

“Sir Robert McAlpine is again trading profitably with a robust structure in place and a strong order book,” the firm added.

The major players were not the only companies hit by losses.

Spie posted a £24.1m loss, following a loss of £13.5m the year before. Enserve’s losses grew from £12.9m to £20.5m and John Sisk reported a £17.8m loss after previously achieving a £1.6m profit. McLaren Construction dived into the red to the tune of £15.4 after a £4.3m profit in the preceding 12 months.

In the concrete frame sector – where financial problems had previously claimed PC Harrington – Byrne’s losses trebled from £4m to £12m, and Ardmore’s deficit more than doubled to £12m from £5.7m.

But a mention should go to some of the other companies who have practised good husbandry and are seeing the benefit on the balance sheet.

Keepmoat – another company with a large housebuilding operation – saw revenue pass the £1bn mark for the first time and its £54.1m return puts it ninth in the table for profit.

Bowmer & Kirkland grew profit 44.5% to £39.1m on increased turnover of £848.2m. Watkin Jones, despite revenue remaining flat at £255.2m, more than doubled its profit to £29.5m and OHOB (O’Halloran & O’Brien) enjoyed an 86.4% rise in profit to £17.8m on turnover of £204.5m.

These companies hadmargins well above the Top 100 average of 1.6%. It remains to be seen if the contractors still struggling with the legacy of recession can flush out their problem contracts and start nudging margins upwards.

Balfour Beatty seeks new direction while Carillion steers a steady course

Under new chief executive Leo Quinn (above), appointed in October 2014, the UK’s biggest contractor, Balfour Beatty, is now almost two years into its recovery programme, dubbed ‘Build to Last’.

Balfour’s problems stem from a plethora of problem contracts which were secured during the recession era. Quinn said that good progress is being made on closing these out; of the 89 identified in 2015, 81% of them are now at practical or financial completion. Without the impact of losses on these projects, Balfour’s construction business would now be close to break-even, the chief executive said, with an underlying profit of £7m returned for the group in the first half of 2016.

“By concentrating on our selected markets, we are growing our order book within a control environment which ensures that our business decisions lead to sustainable profit and cash growth,” said Quinn. “By the end of 2016 we will have successfully completed Phase One [of Build to Last]. Over the following 24 months, I am confident we can reach industry-standard margins and then build on the foundations Build to Last has put in place to deliver a Balfour Beatty with market-leading strengths and performance over the longer term.”

With the order book rising 7% to £12.4bn, the firm’s pipeline looks healthy, and Balfour’s prospects look healthier than at any time in the past three years.

However, the group’s total debt stands at £966m, up substantially from £585m a year ago, and Company Watch’s H-Score for Balfour Beatty has dropped to just 20, against a Top 100 average of 51.1. So it may be a little early to say that the company is out of the woods.

In stark contrast to Balfour Beatty’s continuing struggles, rival Carillion has shown most major contractors a clean pair of heels with increased revenue and a much-improved profit margin of 3%. Carillion shareholders must be feeling well pleased that their company’s proposed takeover of Balfour two years ago ultimately failed.

Carillion chief executive Richard Howson (above), said: “Although trading conditions in some of our markets are still recovering, we continue to see signs of improvement, especially in the UK. The group’s order book and pipeline of contract opportunities both remain strong. Therefore, we believe the overall outlook remains positive and the group continues to be well positioned to make further progress in 2016.”

Company Watch CEO Denis Baker looks at the performance of the UK’s leading construction companies.

This has been a good year for construction: turnover is up and so are profits - all without a significant increase in the size of the balance sheet, suggesting that the sector is working its capital more effectively. But as ever, some individual companies are better prepared than others.

The difference between those companies with high H-Scores and low H-Scores is largely down to three things: profitability, funding, and net worth.

The average profit for the 10 healthiest is over £20m while for the bottom 10 it is only £5m, and all but four are loss-making.

In terms of funding, the bottom 10 companies are much more dependent on debt and this is reflected in the net worth. Three of the bottom companies – Morrison, Sisk and City Building – have negative net worth. This number increases to six when ‘tangible’ net worth is considered (this being simply the net worth of the company when non-physical assets such patents, brand names and, crucially, valuations of acquisitions are omitted).

Our results seem to suggest that there is no real sign of improvement for Balfour Beatty yet; in fact the year-on-year H-Score reflects the continuing downward trajectory of profitability.

The stand-out performer is Skanska, which continues its good performance of the past five years. It has a well structured balance sheet and steady profit.

H-Score

Company Watch calculates a health rating (H-Score), based on published financial information which is processed through a mathematical model to produce an H-Score out of a maximum of 100.

Scores between 76 and 100 indicate robust financial health. A score below 50 indicates financial weakness and those with a score of 25 or less are in the Company Watch danger zone.

Not every company in the danger zone fails but, the past 15 years, almost 90% of all UK businesses that went into insolvency or underwent a financial restructuring were in the Company Watch danger zone at the time.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk