Towards the end of last month West Lothian council approved a £10m programme to fix structural issues at three primary schools.

The schools – Knightsridge Primary in Livingston, Our Lady’s in Stoneyburn and Windyknowe Primary in Bathgate – require the replacement of roofs made of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) panels. The pupils at the affected schools were relocated to neighbouring schools in November 2022 following a structural report.

The discovery of RAAC panels is a serious cause for concern in any building because these products are all life-expired and prone to failure. The problem is especially acute in the school estate, where the material was used extensively.

Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) was invented in Sweden during the 1920s as a significantly lighter alternative to traditional concrete mixes. The material will be familiar to most people in construction, having been used primarily to make lightweight masonry blocks of the type still commonly used today.

AAC contains no aggregate and resembles the familiar Aero chocolate bar: full of bubbles.

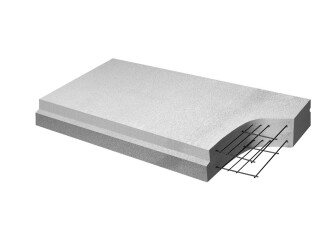

By the early 1930s steel reinforcement had been incorporated to create RAAC, allowing for the production of significantly larger structural units such as wall panels, and floor and roof planks.

RAAC products were first introduced into the UK market in the 1950s and right up until the 1990s were widely used in the construction industry. Due to its light weight, fire resistance and thermal performance, RAAC became popular for use in roof decks and was extensively used as such in both commercial buildings and, particularly, in public sector buildings such as schools, colleges and hospitals.

But RAAC cannot be compared with normal concrete. It is significantly weaker and, due to its porous nature, the steel rebar in RAAC is more vulnerable to corrosion and needs a coating of latex cement or bitumen to protect it.

The aerated concrete also bonds poorly with the reinforcing steel, requiring welded crossbars to secure it in place.

In late 2018 the Local Government Association and the Department for Education sent out an alert to all those responsible for school buildings following the partial collapse of a roof at Singlewell Primary School in Gravesend, Kent.

The flat roof above the school staff room collapsed, damaging toilets, computers and furniture. Luckily, the collapse happened out of school hours and nobody was hurt. But signs of structural stress appeared only 24 hours before the roof gave way.

A 2019 safety alert from the Standing Committee on Structural Safety on the failure of RAAC planks recommended that all those installed before 1980 should be replaced.

The use of RAAC planks and panels ended in the mid-1990s as knowledge grew about the material’s durability, or lack thereof. In 1996 the Building Research Establishment (BRE) published an information paper stating that excessive deflections and cracking had been identified in many RAAC roof planks and there was evidence that reinforcement corrosion had occurred.

In 2002 the BRE released further information on the performance issues of RAAC roof planks advising that, although in-service performance was judged to be satisfactory, it would be prudent to monitor their actual performance after a number of years.

BRE estimated that the lifespan of RAAC roof planks was about 30 years. As this construction was last used in the mid-1990s, even the most recent RAAC roof decks are now nearing the end of their lifespan and most are already life-expired.

Garland UK, a Bristol-based specialist roofing contractor, is keenly aware of the problem with RAAC roof decks and says that the scale of the problem has yet to be fully understood.

“We have always been aware that there are problems with RAAC decks, but the recent alerts have raised general awareness in the industry,” says Ben Whitemore, the company’s technical product manager.

Whitemore explains that about 90% of Garland’s workload is refurbishment and that the company has seen a big increase in demand for the replacement of RAAC roofs over the past three or four years.

“When any roof is stripped and replaced the owner has a duty of care to assess what’s underneath. Now more people know they need to act if they find RAAC,” he says.

“Nevertheless, the problem still isn’t widely known by facilities managers. We are still in the process of educating our clients,” he adds.

Whitemore says the Garland received five enquiries to replace RAAC roof decks in the past year. “Most were known or suspected, but one was unidentified and it was us who identified it,” he says. He expects far more enquiries of this nature this year as awareness of the problem increases.

“People didn’t keep records the way they do today, so it’s difficult to assess the scale of the problem. And that’s the scary thing: nobody knows how many of these dangerous roofs are out there,” says Whitemore.

WHAT IS RAAC?

RAAC products are formed by first mixing cement, lime, extremely fine sand or pulverised fuel ash and calcined gypsum.

Aluminium powder and water are then added to form a concrete slurry, which is then cast in a mould containing the steel reinforcement.

The aluminium powder reacts with the lime and water to produce small bubbles of hydrogen gas that causes the mixture to foam, more than doubling its volume.

When this foaming reaction finishes, the hydrogen evaporates into the atmosphere leaving a lightweight cellular concrete mixture.

Finally, the mould is removed and the product is cured at both high temperature and pressure in an autoclave for around 12 hours. This causes the sand and lime to fuse into a form of calcium silicate hydrate crystal, increasing the strength of the finished product.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk

.png)