When you see concrete paving with loads of grass growing through it, it’ll be one of two things: either the paving has failed catastrophically, or you’re looking at something widely referred to as ‘grasscrete’.

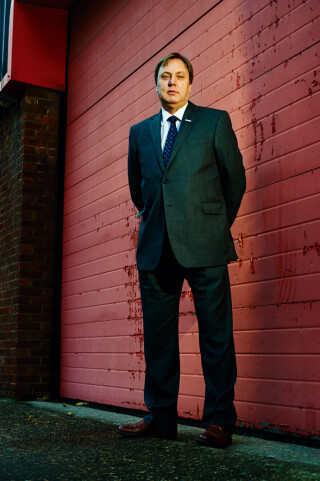

For Bob Howden, the casual use of the term ‘grasscrete’ is a frequent cause of frustration. “It’s the Hoover syndrome – people tend to think that everything grass paving is ‘grasscrete’. But it’s not,” he says.

And that’s because Grasscrete is the name of the main product supplied by the company of which he is owner and managing director: Grass Concrete, headquartered in Wakefield, West Yorkshire.

This article was first published in the Dec/Jan 2021 issue of The Construction Index magazine. Sign up online.

Howden is keen to get that message out, particularly now, as the company is celebrating its 50th anniversary. Over the years, Grass Concrete has exported its reinforced concrete paving system all over the world and currently has 30 licensees serving 65 countries.

Grasscrete is widely used in locations where a strong, durable pavement is required but where the harsh, barren appearance of a continuous concrete surface is undesirable – for example, driveways, access roads and car parks.

But it is increasingly valued for its ability to absorb and contain surface water. With the increasing incidence of extreme weather events caused by climate change, run-off from impermeable hard landscaping is a major contributor to flooding and pollution. A paving product that allows rainwater to soak through rather than run straight off into a surcharged drainage system is far preferable.

Grasscrete was invented in the 1960s by Jack Blackburn, a local authority architect from Huddersfield. He understood the benefit of a perforated concrete paving surface – indeed there were already products on the market. But he also understood the limitations of the existing systems.

These were all precast products laid like any block-paving system. And while they are fine for lightly-trafficked areas they do not perform well in locations like driveways, where traffic continuously passes over the same tracks.

“You get what we call ‘elephant tracks’,” explains Howden, “and that soon becomes rutting.” With precast concrete blocks, this can only be prevented by bedding the blocks in a solid, impermeable base course – thereby compromising the paving’s ability to absorb surface water.

Grasscrete is an in-situ reinforced concrete system and hence much stronger than a block-paved surface. The essential component of the system is the sacrificial styrene mould used to form the concrete structure. This is supplied in 600mm x 600mm units which Howden describes as resembling an “upside-down eggbox”.

The units are laid on the prepared surface to create a continuous mould and standard 200mm x 200mm BS 4483 steel reinforcement mesh is then laid on top with the plastic ‘domes’ of the mould sitting inside the mesh.

Concrete is then poured over the plastic mould and struck off level with the top of the mould. Once the concrete has reached sufficient strength the surface is torched to burn out the exposed plastic on the top. This opens up the voids inside the mould and it only remains to spread topsoil over the paving and seed it.

A neat feature of the system is that the apertures form truncated cones that open out at the bottom to give the roots of the grass plenty of space to grow. A problem with other systems is that restricted root growth weakens the plants which can then die off in dry weather.

“Originally, Grasscrete was valued mainly for its aesthetic properties,” says Howden. “In the 1970s we were into modular construction and system building and the ability to introduce green space into the urban environment was a boon,” he explains.

But in recent years the demand for sustainable urban drainage systems (SuDs) has bolstered demand for Grasscrete and is now one of the main reasons for its use.

While surface water will readily drain through the Grasscrete system, its ability to mitigate run-off depends on what happens below the paving. “It’s not just a case of how fast you can drain the water,” explains Howden.

Some SuDs installations collect surface water and store it temporarily in underground tanks or cellular reservoirs. But Howden says that a drainage blanket and a 150mm layer of no-fines aggregate below the Grasscrete can help maintain natural hydrology. “And you can store water and use it for irrigation,” he adds.

The full potential of grass paving to mitigate flooding was amply demonstrated through Grass Concrete’s Hong Kong licensee during the rapid urbanisation of the New Territories in the 1970s.

Building works led to a massive increase in surface water run-off and regular flooding. The initial approach to tackling this was to create open drainage channels and slopes which were sprayed with concrete to prevent landslip and rock fall.

Not only did this just accelerate the run-off, it also severely compromised the natural fauna and flora, particularly in indigenous wetland areas. Pressure from lobby groups and the creation of a government environmental committee gave Grass Concrete, through its licensee, an opportunity to demonstrate its benefits.

Change began in earnest from 1985 with the construction of the Lam Tsuen River training scheme near Tai Po. Instead of the usual solid concrete construction, this drainage channel was lined with Grasscrete to become not only a reliable flood-relief asset but also the focus of a country park which has developed around it.

At the same time, back in the UK, a need was established to create a clear benchmarking of grass paving systems under heavy water flow.

With a number of systems now available and no formal standard, the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) set out to address this issue.

In 1986, after concluding field trials, CIRIA published The Design of Reinforced Grass Waterways which, amongst other things, established that grass under heavy flow becomes more hydraulically efficient than had been originally understood. A consequence of this was the ability for future drainage channels to be smaller in section, have less impact and be lower in cost.

While Grass Concrete originally just licensed its system to third parties, in the mid-1970s it started to compete with the existing precast systems with its own version, called Grass Block.

Then the company decided to expand into contracting, installing its own in-situ system as well as selling to third-party installers. In 1981, Howden joined the company as contracts director to develop this side of the business.

“One of the reasons for that was that we were looking at how we could control the standard of the installations – because back then, we’d just been supplying the plastic moulds and leaving people to cast on site,” says Howden.

Henceforth the UK business became entirely centralised; the licensee network was dismantled and Grass Concrete undertook every installation. “It gave customers the confidence that the installation was essentially by the manufacturer,” Howden explains.

The contracting side of the business grew rapidly and in 2005 Howden led a management buyout from then-owner Sir Rodney Walker. “As Sir Rodney became less and less executive within the business, I became more executive and that culminated in the buyout.”

Since around this time, the need for flood prevention has proved an increasing focus for Grass Concrete, as indeed has the domestic market overall.

“The UK’s a massive market,” says Howden. “In terms of turnover it accounts for about 85% – by value, that is – not volume. That’s because, with international licensees, what we do is sell them the styrene void formers which of course represent a tiny fraction of the cost of the installation.

“In terms of units, we probably sell an equal amount overseas as we do in the UK, but in terms of the financials it’s probably 15%,” he says.

Howden says the company, which recorded a turnover of about £4m last year, is growing steadily at roughly 10% per annum. Brexit has had a depressing effect, he admits, but Covid-19 hasn’t affected the business too much.

“We’ve worked right through the pandemic,” he says, “and one of the factors there is that a lot of our work is flood-related. That has been classed as essential work and so in most cases that work has continued. We’ve managed to keep going and we’re back to close to normal levels now.

“We’ve just finished a big car parking project for Saracens Rugby in Barnet – that was an 8,000m2 installation. And in terms of flood defence projects, we’ve just finished a project in Pocklington, East Yorkshire and another in Saltash in Cornwall.

“We tend to have at least one flood defence project on the go at any one time and there are a number in the pipeline as well,” adds Howden.

This article was first published in the Dec/Jan 2021 issue of The Construction Index magazine. Sign up online.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk