Each of the two dozen construction sites that serve the Thames Tideway tunnel project in London would make a fascinating standalone case study in logistics and engineering; put together in the context of the overall scheme they underline the scale of the task at hand.

Ongoing work at Albert Embankment Foreshore involves three separate foreshore cofferdams, two major excavations and three lengths of tunnel and is taking place with incredibly limited access and within metres of occupied office buildings. And yet it is just one of 24 Tideway sites in the capital, almost half of which involve some kind of intervention with the River Thames.

While the final result will be a 25km-long tunnel – and its associated supply and control infrastructure – the excavation of the main route is just one facet of this enormous undertaking.

Only a handful of the project sites will see tunnel machines actually arriving at or departing from them – many, like Albert Embankment Foreshore, are required for the construction of the additional infrastructure that will intercept and redirect the sewage that currently flows directly into the river.

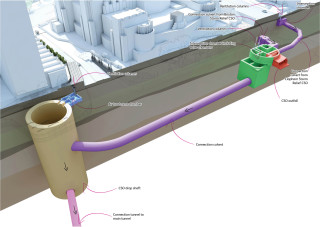

This site involves construction work on both sides of Vauxhall Bridge, where two combined sewer overflows will be intercepted and redirected – one of which originates in Clapham and outfalls on the upstream side of the bridge, and a second from Brixton on the downstream side.

Although casual onlookers will not have seen any of the six tunnel boring machines at the site, Tideway project manager Lee Fisher reveals that Ursula passed through on her way to Chambers Wharf some time ago.

At Albert Embankment Foreshore, the focus is currently on excavating the interceptor chamber into which the overflow from the two sewers will be redirected, and the start of a short connector tunnel that will link the main drop shaft into the Tideway Tunnel.

Construction of the smallest of the site’s three cofferdams, just upstream of Vauxhall Bridge, began at the end of last year. Within it, a local interception chamber for the Clapham sewer will be constructed, and from here a 60m-long, 2.2m-diameter culvert will be driven in the foreshore below the bridge to take the flow into the main interception chamber.

Here it will be joined by discharge from the Brixton sewer, entering a series of chambers which will combine and control the flow before directing it via a 112m-long tunnel to the main drop shaft.

The drop shaft represents the largest of the infrastructure elements on the site, at 17.9m internal diameter and 52m deep, and its purpose is to dissipate the energy of the discharge as it drops down to the main tunnel level, as well as ensuring that as much air as possible is expelled from the flow.

This process is essential to ensure that the tunnel’s capacity can be exploited to the full. Expelled air will be treated before being discharged through ventilation shafts at ground level which will be incorporated in new public realm landscaping that will be built over the shaft on completion.

The final element of infrastructure at Albert Embankment Foreshore is a short tunnel from the bottom of the drop shaft that will carry the discharge to join the flow in the main tunnel just 10m away. When TCI visited the site, work on this tunnel was just starting, with Tideway Central design-and-build contractor Ferrovial Laing O’Rourke creating the pipe arch that will support the top of the tunnel mouth as the drive begins.

Nearly all of the work that is being carried out at this site takes place on the foreshore of the River Thames, hence it involves a substantial amount of temporary works. In addition, like many of the other foreshore sites, highway access is severely restricted by the presence of occupied office buildings.

Consequently, the vast majority of material and equipment is delivered instead to a compound in Northfleet, just downstream of the Dartford Crossing, before being brought to site by river on the weekly barge delivery. This does require careful planning, acknowledges Ferrovial Laing O’Rourke site agent Oliver Smith, but despite his initial misgivings, he believes it works better this way and encourages better planning. There is little room for materials on site, so the barges moored alongside the cofferdam also provide storage.

Construction started on the site in February 2018 with marine piling for the largest cofferdam, which encompasses the site offices, the main drop shaft and logistics area. There is minimal space for vehicle movements and concrete delivery.

This cofferdam acts as the river wall during the works, and hence has been designed by the joint venture’s consultant Aecom to withstand vessel impact, being formed of two rows of sheet piles with backfill in between them. The second cofferdam within which the interceptor chamber is being built has a much smaller footprint, so the contractor opted to use combi-piles as space did not allow for a double wall. These are installed to a depth of around 25m with an 8m cantilever. Ship impact protection has to be provided separately.

While the piling work was going on, the most significant challenge was managing the noise, says Fisher. “Impact piling was the only viable option for some of the piles, and with residential and office buildings very close by, mitigation was necessary,” he explains.

In the case of the office block, this involved the installation of secondary glazing to the majority of the windows overlooking the site – and two acoustic cameras were used to assess the impact of vibratory equipment so that the source of any noise could be accurately identified and mitigated or shielded. Fisher believes that this is the first time such cameras have been used on a civil engineering application.

Around 1,100 tonnes of sheet piles and 34 tubular piles were installed for the two cofferdams – all of them from the two jack-up barges that are central to the contractor’s fleet on this site. One of the barges remains on site, servicing the smaller cofferdam with craneage to free up operational space within it.

Two floating crane barges, two delivery barges and a dedicated safety boat make up the rest of the fleet, with three tugs, called Multicats, shared between all the sites on this contract. The main marine piling was completed just over a year later, in March 2019, and since that time, construction within the main cofferdam has focused on the drop shaft and the connector culvert to the interception chamber.

The top 26m of the circular drop shaft was built using secant piles of 1.3m diameter to extend the full depth of the London Clay; the shaft itself sits within a ring of permanent steel piles that will form the boundary of the new river wall once the construction is complete.

The lower 21m of the shaft has a sprayed concrete primary lining, and was excavated a metre at a time down to full depth to enable the 3m-deep base slab to be poured. Tunnelling towards the interception chamber began when the shaft reached the required depth – around 20m – and with a Cantideck (a cantilevered crane loading platform) installed at the portal for access, work on the tunnel and excavation of the shaft could continue in parallel.

While this benefits the programme, working on two faces through a single shaft makes lifting operations more risky and a ‘traffic light’ system with lifting and exclusion zones has been installed to reduce the risk. A string of LED lights around the edge of the shaft turns red when the crane is lifting, giving staff a visual cue that there is increased risk, returning to green when it is finished.

Smith explains that plans to build the connector culvert to the interception chamber with a TBM were shelved in favour of spray-concrete lined (SCL) construction which was deemed quicker: “With a TBM we would have had to halt work to bring it back out once we reached the end of the drive,” he explains.

SCL construction enabled the crew to follow straight on with the tunnel waterproofing – a membrane system from Soprema – and the secondary reinforced concrete lining, built in situ using formwork, is now well advanced. Most of the invert pours and about a third of the crown pours had been completed when TCI visited in January. A similar construction process will be used for the short tunnel that links to the main drive.

Smith estimates that excavation of this tunnel will take a week or so. “But of course that will depend on ground conditions. We were lucky with the longer tunnel – it was in clay and conditions were very good,” he says. In fact Fisher reveals that it was delivered six weeks early in a 13-week programme, with the use of the Cantideck contributing to this.

The shorter tunnel is being driven through the Lambeth Group and, with the possibility of sand pockets, could be more troublesome, suggests Smith. Meanwhile from the end of January onwards, the crew in the drop shaft will start to build the secondary reinforced concrete lining, working back up to the ring beam at ground level.

In the second cofferdam, closer to the bridge, top-down excavation of the interceptor chamber is the main activity. The chamber has a number of different levels and extends to a depth of some 20m – the first cascade slab has been placed and excavation beneath the slab is now under way. Smith reveals that this contractor’s alternative to the open excavation will also save time in the programme.

Initial plans for construction of the works upstream of the bridge were revised to minimise disturbance to the residential blocks on the riverside. A larger cofferdam was initially proposed within which the connector culvert was to be excavated. But the many constraints at the site made a rethink appropriate, and the culvert will now be built by pipe-jacking from a 10m x 10m cofferdam launch chamber. A second chamber will be built for the diversion works next to the outfall itself.

Fisher says: “We would have been installing piles just a few metres from the Victoria Line tunnel, which was a concern to London Underground, and there was also the potential disturbance to residents from out-of-hours working.”

While construction progresses, there are still challenges to resolve ahead of final completion in a couple of years’ time, says Fisher. The exact procedures by which the sewer discharges will be permanently diverted into the new system are still being devised, and the best method of removing the cofferdams – which again must consider the impact of twice-daily water level fluctuations – are still under discussion.

Time and tideway

The £3.8bn project under construction between Acton in west London and Beckton in the east will intercept the most polluting storm overflows and reduce the amount of raw sewage that washes into the River Thames following heavy rain. Construction work started in 2016 and is due for completion in 2024.

It is being financed and built by Tideway/Bazalgette Tunnel – a consortium of infrastructure investors Allianz, Amber Infrastructure, Dalmore Capital and DIF – and will be maintained and operated by the same body.

Tideway has four main delivery partners: three design-and-build joint venture contractors responsible for work in the east, central and west regions, and a fourth responsible for the process control, communication equipment and software systems for operation, maintenance and reporting across the whole system.

Tideway West, building Acton to Fulham, is a joint venture of BAM Nuttall, Morgan Sindall and Balfour Beatty Group.

Construction in the central region between Fulham and Blackfriars is being carried out by Tideway Central, a joint venture of Ferrovial Agroman UK and Laing O’Rourke Construction.

The third joint venture of Costain, Vinci Construction Grands Projets and Bachy Soletanche covers Tideway East, from Bermondsey to Stratford.

The system integration contract was awarded to Amey.

Tunnels and river use

In March 2019, Ursula became the second TBM to be launched on the project, starting from a 45m-deep shaft at Tideway’s biggest construction site at Kirtling Street (above) in Battersea and heading east to Blackfriars Bridge Foreshore. From there she will continue to Chambers Wharf in Bermondsey.

In total there are six TBMs – four for the main tunnel drive, and two for smaller-diameter tunnels that connect into it. Millicent started her 5km westward drive from Kirtling Street at the end of 2018 and arrived at Carnwath Road within a year.

Rachel left Carnwath Road last year and is currently tunnelling 7km westwards towards Acton, and Selina will drive the eastern section from Chambers Wharf to Abbey Mills. Annie and Charlotte are responsible for the smaller drives.

With many of the sites being on or close to the river, one of Tideway’s key construction commitments was to use river transport for material delivery and spoil removal, reducing lorry movements considerably.

Last October Tideway reported that a million tonnes of excavated tunnel material had so far been transported from its Kirtling Street site by 710 barge movements; this is replicated on a different scale at Albert Embankment and elsewhere. Spoil is sent to Ingrebourne Valley’s Tilbury Ash Disposal site and Rainham for beneficial reuse.

Tunnel lining segments are also brought in by barge to the Kirtling Street site from a precasting site on the Isle of Grain in the Thames estuary.

Thank you for reading this story on The Construction Index. Our editorial independence means that we set our own agenda and where we feel it necessary to voice opinions, they are ours alone, uninfluenced by advertisers, sponsors or corporate proprietors. Inevitably, there is a financial cost to this service and we need your support to keep delivering quality trusted journalism. Please consider supporting us, by purchasing our magazine, which is currently on sale for just £1 per issue. Order now.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk