Brilliant though BIM is as a design and modelling tool, it has yet to have a significant impact on the fundamental reasons behind inefficiencies in construction, claims Ali Mafi, partner at project management consultancy Lean Thinking.

Far greater savings would come from speeding up the construction process: time accounts for 80% of the project cost yet little effort is spent on addressing the amount of time wasted, says Mafi, citing 15 years of data collected by the firm.

BIM does bring benefits, he concedes – for instance, in allowing clients to walk through their proposed projects and confirm what they will be getting. But he says that there is little, if any, evidence that the industry’s shockingly low levels of productivity have in any way been turned around through its use.

Instead, says Mafi, time compression should be construction’s driver and the foundation for transforming its performance. National key performance indicators show that more than 60% of projects run late; “but clients I work with claim it is around 80%”, he says. This is despite the introduction of new forms of contract and modern techniques such as BIM and off-site construction.

Most of construction’s improvement efforts are focused on the physical infrastructure, with BIM and value engineering used to change the design – yet the cost of building materials is only roughly 20%-30% of the project cost, says Mafi. “The other 80% is then left untouched.”

Mafi says that even projects that finish on time tend to do so with quite a lot of stress and expense. If time is lost every week, people will end up working weekends and nights in the project’s closing stages. Moreover, the very meaning of ‘on time’ is usually open to interpretation: “When contractors say they have finished on time, it’s generally because they’ve managed to pin all the delays onto the client and apply for an extension of time,” says Mafi.

Almost all delays are blamed on the client, usually because of changes to the design or through slow decision-making. But Mafi says that, according to data amassed by Lean Thinking, less than 30% of the delays are actually due to clients.

For those unfamiliar with business-speak, ‘lean thinking’ is the modern name given to the organisational approach pioneered by Japanese car-maker Toyota to maximise production efficiency. Mafi is a ‘lean thinking’ expert with 35 years of construction experience who, though his appropriately-named consultancy, has spent the past 15 years advising project teams on how to compress project time.

Lean Thinking’s client list includes British Land, Network Rail, Balfour Beatty, ISG and a number of county councils and water utilities.

Mafi’s firm helps projects make better use of time. “We believe that 50% of the duration of almost all projects is made up of time risk allowances and that virtually all that ‘safety time’ gets misused, even if the risk does not materialise,” he says.

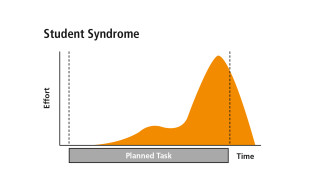

Everybody adds a bit of time to every task: “They call a seven-day task 10 days – but there is around an 80% chance that ‘student syndrome’ will kick in,” he says. “They then leave it until the last possible moment.” Even if the duration of all the tasks is doubled, student syndrome would still mean late running unless the time risk allowance is dealt with in a different way.

The ‘Monday start’ is another problem that wastes time. “Everything has to start on a Monday in our industry,” says Mafi. If someone finishes a task on a Tuesday, chances are that the following trades will not be lined up to start until the following Monday. “The Monday start alone costs projects around four weeks a year,” he says.

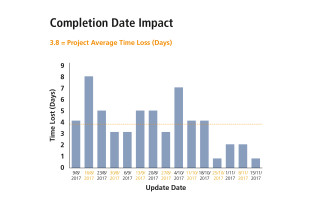

Mafi has analysed data from a sample of major projects across various sectors that Lean Thinking has been working on recently. The analysis showed that, on average, project completion dates had been slipping by two days a week – though in some cases this would be covered by those generous time risk allowances built into the schedule.

These losses come from delays to the critical path from issues like people not turning up, not having the right materials, bad weather or waiting for plant. This loss of time can make the difference between profit and loss – and can also trigger penalties.

A particular bugbear for Mafi is that he believes that operatives on site generally only work for about 30% of the time, which he finds particularly frustrating given all the talk about labour shortages. He will see people wandering past, apparently en route to breakfast, hours after the break should have been taken. “Let’s get everybody up to 40% and we’d see a massive improvement,” he says.

Lean Thinking has developed a standardised system for managing, monitoring and controlling progress. Projects use the approach to ensure work is done to a strict schedule and that the remaining number of days to completion are closely monitored.

Twice a day, the system highlights any shifts in the end date and forces people to take action. The key issues are to remain clear about whether work is correctly prioritised and whether it is being done in the most effective way. Mafi likens it to a satnav system that is updated to show arrival time in response to the driver’s progress and traffic delays ahead.

“If you aren’t aware every day of the impact of your work on the end date then you are not managing the project and you have a 70%-80% chance of running late,” he warns.

Mafi says that the use of time tracking and ‘4D’ modelling to introduce time to a BIM system is likely to give an inaccurate picture of progress unless changes in the projected completion date are factored-in as the work progresses. A 10-day task that is 50% complete is generally deemed to have five days remaining. But this doesn’t take into consideration how spread-out those days have been or will be.

Lean Thinking advocates measuring elapsed time – including any days when work didn’t take place – and combining this with updated projections of the time that will elapse before completion. Designers are the worst for this, Mafi finds. They might have spent 10 days on a task – but it might have taken them 30 days to do those 10 days.

“As part of progress monitoring, we predict the total elapsed time by asking how many days until the task will be complete,” he says. “We ask the person who is doing the work ‘when are you going to finish that?’.” The answer might be weeks rather than days – because some of the parts are missing or a holiday is scheduled.

As a result, the true progress may be rather less than had appeared using conventional measures – a 10-day task might suddenly become a 40-day one. This elapsed time approach is the most accurate and scientific way of showing time to completion and the end date, Mafi says.

The industry is paying a lot of attention to the information add-ons that turn 3D modelling into BIM, but Mafi thinks this needs to be looked at. The issues affecting the industry can’t be solved just by introducing BIM, he says.

According to Mafi, BIM’s cloud-based collaboration capabilities are currently providing very little benefit at the design stage, except for clash detection, but could act as an enabler for a radical improvement of the process. Collaboration could be used to enable a shift towards a concept called ‘one-piece flow’, which can save time and boost quality.

‘One-piece flow’ - also known as ‘one by one’ - involves working on things one at a time. The simplest example is to consider 100 identical newsletters that have to be popped into envelopes, sealed, stamped and given address labels. Most people – about 90% – would tackle this by doing each task in sequence on all 100, starting with filling all 100 envelopes – known as ‘batch and queue’. However, this means handling each envelope several times.

The alternative is to do all the steps for one envelope before moving to the next. Working on something continuously – one by one – has been shown to be 50% quicker and take less effort.

In a building context, an electrician won’t generally come to the site until there is a lot of work to go at, says Mafi – say 10 rooms. But there may be benefits to coming when the first is ready – for instance, it might be cheaper in the long run if the task is on the critical path and cost penalties are at stake. “Saving time is not the only benefit – an error will be picked up far sooner,” he says. If you label the envelopes upside down – or install the wrong light switches – you might not notice until all had been done.

Current design practice is based on the ‘batch and queue system’ – like filling all the envelopes before moving on to applying the stamps. “One-piece flow means you deal with something until you have finished with it,” says Mafi. “At no point does the work sit there waiting - you do exactly the same amount of work in half the time.”

An obsession with trying to keep everyone busy means that work tends to be batched up, says Mafi, with people working in isolation. “This is what happens in design,” he explains. “That’s why there are so many errors – everything is batched up and everything sits there waiting.”

But this can be addressed and he sees great potential benefits from an approach used in car manufacturing. Essentially, everyone works together in a real or virtual ‘big room’ or ‘war room’ – also sometimes known by the Japanese term obeya, the approach adopted by Toyota and other Japanese car manufacturers.

Using BIM via the cloud can create a virtual ‘big room’. “As you do your work, others are watching and can say if it won’t work. You work a bit at a time and pick up issues like clashes sooner rather than later,” explains Mafi.

He sees BIM’s benefits as stemming from 3D modelling, rather than all the add-ons that bring in time and data. “People think that the more you break things down when planning a project, the better the chance of finishing the project on time,” he says. “But there is more to it than that.”

In particular, he feels that clash detection – often a focus for BIM on projects – is wasting a lot of money. Large sums are spent by contractors going over the BIM models when the project arrives on site, but they might as well simply accept that some adjustments will be needed.

According to Lean Thinking’s project data, close to 90% of potential clashes could be resolved simply by making minor adjustments at site level. “Some projects spend over £100,000 detecting clashes, most of which could just be dealt with on site like in the old days,” says Mafi.

Contractors are starting to realise this, he says. One recently told him that it had stopped clash detection as it was costing too much, particularly as most clashes have only minimal impact. “Part of what we do is monitor delays on projects,” says Mafi. “I can think of only two projects in the last 15 years where there have been some delays to the critical path as a result of a clash.”

For many BIM enthusiasts it might come as a shock – even a disappointment – to learn that even relatively major clashes don’t usually have an impact on the end date.

Mafi is also concerned that increasing adoption of BIM could end up becoming a bureaucratic add-on, rather than a value-added tool for radical performance improvement. “There is no proof that projects are coming in early because of BIM,” he says. Furthermore, BIM is adding overheads, he finds. In this respect he likens it to ISO 9001.

A problem is that additional resources are having to be brought in to manage BIM. “Many companies are finding that a lot of their design managers’ time is being taken up dealing with BIM and sometimes they are having to add extra resources,” he says. This has a negative impact on productivity: greater input into running the project does not yield much – or any – increase in output, he says.

In its drive to promote the adoption of BIM, Mafi would like to see the government focusing more on how projects can make use of BIM to save time, “not just telling people to use BIM with the assumption that they are going to compress time”.

As part of this, he would like to see promotion of ‘one-piece flow’ and for people to be made more aware of issues such as the ‘student syndrome’ and how BIM can help with them.

This article was first published in the December 2017 issue of The Construction Index magazine, which you can read for free at http://epublishing.theconstructionindex.co.uk/magazine/december2017/

UK readers can have their own copy of the magazine, in real paper, posted through their letterbox each month by taking out an annual subscription for just £50 a year. See www.theconstructionindex.co.uk/magazine for details.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk