Changes to the way VAT is collected in construction could affect up to 150,000 organisations and will cause cash-flow problems in an already squeezed sector.

In roughly a year’s time, HMRC will change the way it collects VAT from construction organisations. If not properly planned for, the new regime could push small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) into an even greater cashflow crisis and force large contractors into bureaucratic limbo. The government estimates that between 100,000 and 150,000 companies will be affected.

The driver behind these sweeping changes is the government’s mission to clamp down on a particular type of crime known as ‘missing trader fraud’. The scam has migrated across several industries, and is now taking root in construction supply chains.

Missing trader fraud is a simplified version of an international scam known as ‘carousel fraud’. But whereas carousel fraud operates across country borders – exploiting the import of VAT-free goods from one country, then selling them on to a series of companies, and possibly even back to the original seller – missing trader fraud is confined to the UK.

Fraudsters exploit weaknesses in the labyrinthine VAT system to steal government money. Under normal circumstances, a subcontractor will charge the main contractor for work carried out, adding 20% VAT. Every quarter, the subcontractor declares the VAT, paying it back to HMRC. So far, so straightforward. But as the product or service moves up the supply chain, bits of VAT are added at each new transaction, and subcontractors claw back VAT that they have paid their suppliers.

Seasoned criminals have found lucrative ways of tapping into this cash merry-go-round, taking over organisations or setting up fraudulent shell companies and then providing services, often in the form of labour, to a project.

Tax expert Liz Bridge is secretary to the Joint Tax Committee of Construction which represents many industry federations. She says that companies in missing trader fraud will initially operate normally but, after being paid for the work, will disappear without filing their tax returns and without paying the VAT money, which has effectively been stolen from the exchequer. Such bogus companies tend to operate for between six and nine months before vanishing without trace.

Although construction projects are a relatively new target for missing trader fraudsters, the scams have operated in other sectors for more than a decade. They started in the trade for electronic goods, such as laptops, computer chips and mobile phones. As the authorities increased measures to fight off the fraudsters, criminals moved into new sectors, including precious metals and wholesale electricity trading.

Now missing trader fraud is infiltrating services such as the supply of construction labour. As Richard Asquith, vice president of global indirect tax at tax technology firm Avalara points out, this presents an added challenge to HMRC. “There are no physical goods. You can’t trace them and find them in a warehouse. With delivery of services onto a construction site, it all evaporates instantly.”

Bridge explains that the fraud is usually controlled by industry outsiders.

“It’s sophisticated, orchestrated and may involve money laundering. It’s not carried out by people working in construction, but by those with sufficient industry knowledge and some construction connections,” she says.

Bridge explains that the fraudsters often enter the sector by targeting small-business owners and tradesmen who are at the point of retirement:

“If someone has been trading for 35 years as a respectable plumbing business, their company may not be very saleable, but may have a good pedigree. A dodgy accountant could introduce them to someone who offers to buy the company for a small amount, transferring the shares over to them.”

Bridge describes the legitimate business owner as a patsy: typically, they will not knowingly be colluding with crime, but will have been duped by fraudsters who want the company “as a kind of camouflage, because of its high pedigree”. They will have no idea that the new incarnation of their company will be shut down in under a year.

Although the number of criminals carrying out this kind of scam in construction is relatively low, they are believed to be making a significant dent in government coffers. The government calculates that it loses around £13bn to missing trader fraud annually with construction accounting for £100m in lost VAT. But as Bridge points out, this is a fantasy figure as “HMRC can’t count the money that it has been cheated of”.

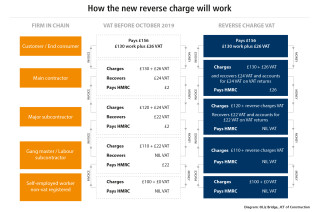

Nevertheless, the whole of construction will have to bear the brunt of the government clampdown. A new reverse charge taxation system will be imposed on the sector from October 2019. Under this new procedure, VAT cash will no longer flow between businesses. With each business transaction, the VAT will be calculated as a paper exercise and registered on the invoice as a ‘reverse charge’. Only client-facing organisations at the top of the construction supply chain will be required to pay the tax.

As a general rule of thumb, any company that is registered with the Construction Industry Scheme (CIS) – HMRC’s construction-specific tax-collecting regime – will fall into the reverse charge category. Any company that is invoicing a client that is not CIS-registered must charge VAT.

This has several major implications: the first, that small and medium-sized businesses will no longer be able to rely on VAT money for cashflow; the second, that the onus will fall on major contractors to pay very large sums of money to the exchequer. And the third is that the whole of industry will need to get to grips with a new accounting system, or risk being mired in complex red tape. Potential accounting errors could push some organisations to unsustainable levels of debt.

“Contractors’ initial response to the legislation was that they didn’t fancy it. It was going to cost a lot of money and effort,” Bridge comments. “But they don’t have a choice, it’s coming anyway.”

Andrew Dixon, head of policy at the Federation of Master Builders, says that the new policy will have a mixed effect on members. Many of the FMB’s members are sole traders and small firms that work directly for houseowners and domestic customers. They will continue to charge VAT, because the customer is outside of the construction sector. But those that are inside construction supply chains will need to change their accounting systems and prepare for a dwindling cashflow.

“They need to plan for that and make sure they are ready for it,” he says.

Asquith is concerned for the welfare of the many small companies that have for years effectively relied on VAT loans to keep them afloat. But Bridge is less sympathetic: “A well-run company never pays its VAT late, and never has to wait until it is paid to get the VAT money over,” she says. “Effectively, if you use the VAT, you are borrowing from the state – unarranged and without interest. There aren’t many cases in business where that kind of transaction would be allowed.”

Larger organisations may have to grapple more frequently with the question of whether they may have to pay or reverse-charge VAT in each situation, particularly as their role can shift in a changing commercial climate – for example, switching from builder and developer to owner and landlord, if a property is not sold.

But Bridge believes that, by moving the onus for payment up the supply chain to the largest players, which interface with customers, it will be harder for companies to evade paying VAT in general.

“The largest companies have professional tax advisors. They can agonise about whether the organisation is acting as a customer or not,” she says.

But all agree that a major push is needed to educate the sector on these changes.

“Realisation hasn’t hit yet. We’re trying to raise awareness with our members, because companies need to start preparing for it,” Dixon says.

Bridge adds: “Once industry has got its head around this, I don’t think it’s going to be technically difficult to do. But what frightens me is that companies don’t take tax changes seriously. It’s not just about educating people, the software houses also need 12 months to prepare for the change, people need to start saving now.”

The new reverse charge

The new reverse charge VAT system will apply to the construction sector from October 2019.

The government has put out a consultation on how the new system should be implemented, which concludes in October 2018. After this, accountancy software providers have just twelve months to create and roll out new IT packages that conform to the new regulations.

Tax expert Liz Bridge estimates that construction companies will need a minimum of ten weeks to implement the new systems internally. She is concerned that subcontractors that do not adapt to the new system in time could make costly mistakes on their invoices.

“If suppliers accidentally charge VAT to a main client, they will have to reverse that invoice out of their accounting system,” she warns.

This is not as simple as it sounds, because as soon as VAT is raised on an invoice, it is owed to the state.

Bridge explains: “The analogy I’d use is when you’re knitting, and some of the knitting is falling off the needle. It’s much more difficult to teach people how to pick up dropped stitches, than to teach them how to knit.”

Large contractors will also face challenges in ensuring that they avoid expensive VAT errors. “They’re dealing with very large sums of money now. They mustn’t invoice for VAT when they aren’t going to get it back from the customer, because this could tip them over the edge,” Bridge warns.

She would like to see an online system where users can automatically check whether their customer is CIS registered. This would provide essential support to non-tax specialists, such as small company owners who do their own accounts.

“I’d like to see a system that can be run by accounting machines, that automatically creates a reverse charge invoice,” she says.

At the top of supply chains there is going to be an element of wrangling as to which companies will have to pay the VAT.

Richard Asquith, of tax compliance software firm Avalara, points out that companies often provide bundles of services and it is not always easy to ringfence those that fall into the construction category. He predicts that HMRC will create a “long and very prescriptive” list of companies that are liable to pay the tax.

“There’s going to be a wrangle between industry and HMRC about what’s in and out of the list and, inevitably, it will be too broad for fear of missing anyone out,” he says, adding: “Sometimes it can turn into a sledgehammer to crack a nut.”

This article was first published in the September 2018 issue of The Construction Index magazine

UK readers can have their own copy of the magazine, in real paper, posted through their letterbox each month by taking out an annual subscription for just £50 a year. Click for details.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk

.png)