Michael Krajewski planned many careers before he fell into construction. The Polish national, who grew up in South Africa, always dreamed of becoming an army officer; failing that, an aeronautical engineer.

He tried both, without success. So now he’s running a start-up based on an industrial estate outside Hounslow, west London, fabricating structural steel parts.

Krajewski came to the UK to improve his English. In his mid-twenties, he was still trying to get into the Polish military while working for a small engineering firm near London. After being rejected again, he decided to start his own business.

“Structural steel seemed the obvious choice because it’s short-term. You can put in an order, and one week later it’s done and dusted,” he says. He also realised that steelwork resonated with his personality. Having worked on a building site as a student, he “loved putting up walls, but hated plastering and decorating”.

Starting out in 2009, Krajewski’s first idea was to become a consultant, sourcing steel parts for large projects, whilst also managing the logistics and installation. With recession gripping the country, it was a tough moment to start any business. Even tougher for someone not yet thirty and with no commercial track record.

“No one wanted to pay me a deposit. I had just £12,000 in capital, which were my own savings,” he recalls.

He soon realised that becoming a fabricator would be an easier route in. And, having experienced the dazzling robotic and CNC technology employed in the aeronautical sector, Krajewski sniffed an opportunity for introducing innovation.

Today Steelo’s semi-automated plant turns over nearly £4m and employs 30 people, supplying small projects mainly in the south-east of the UK, and mostly in the residential market. This bread-and-butter work funds Steelo’s research into more exciting areas such as 3D printing, but Krajewski – who in some circles has acquired the sobriquet “the Steel Guy” – has been innovative from the start.

You can see this in Steelo’s responsiveness to client requests. Lead times between placing an order and delivery to site can be as short as one day, with the parts reliably arriving within a two-hour time slot.

This seems extraordinary for a company the size of Steelo, but Krajewski says that it’s all down to automotive-influenced lean manufacturing principles, supported by a bespoke IT system. Also, he adds, “we’ve adopted the theory of constraints”.

This is a manufacturing theory, developed by Israeli business guru Eliyahu Goldratt, that looks holistically at the manufacturing process, prioritising the loosening of bottlenecks in production. The focus is on how a company makes money as a global entity, rather than how efficiently each machine performs.

Thus, according to the theory of constraints, a machine might be under-utilised or departments overstaffed.

“In our theory, you want one department to be working at 100% capacity, and the rest of the business to be under capacity. This is beneficial, because if there’s a problem, it’s likely to be in the department that is working at 100%. So other departments can take up the slack,” he explains.

Krajewski originally thought his production bottleneck would be in the welding bays. But when he started studying Goldratt’s theory in earnest, he realised that the company’s most vulnerable point was its delivery.

“If we break something in the factory, we can always stay long, work overtime, add resources,” he explains, “but if we’re late with the delivery we’ll never make up the time, because we’re often restricted to between the hours of 8am and 5pm due to council restrictions.”

To ease production glitches, many of Steelo’s staff are multi-skilled, jumping into alternative roles as required. In the office, designers can cover for estimators, whilst those working on the factory floor are trained to do many different tasks.

The balance of the workforce is also unusual: only half the team is involved with production and logistics, whilst the other 50% is office-based. Krajewski acknowledges that an office-heavy workforce “might seem like dead wood” to other manufacturers but explains:

“It’s how we implement innovation. Some of our office-based employees are solely focused on innovation or improving operations.”

The factory floor looks surprisingly empty when TCI visits. Steelo holds roughly two to three days’ worth of its steel stock requirements.

“Newcomers are always surprised by how little steel we have,” Krajewski says, “compared to how much goes through our production.” Steelo completes between 10 and 15 orders a day on average, turning around up to 200 tonnes of steel a month. “But we don’t want lots of stock clogging the system. The important thing is flow.”

The company’s bespoke IT system is at the heart of all operations, prioritising the order in which each task must be completed, issuing instructions to the design department and factory floor. The IT system also tracks deliveries and orders and will reject short-term orders if the system has hit capacity.

“I did shop around for readymade ERP [enterprise resource planning] packages, but then I realised that we’d have to fit our operations into how the software works,” Krajewski says, adding that most ERP packages have been developed for repetitive manufacturing, and are less suited to the bespoke requirements of construction projects.

More revolutionary is Steelo’s approach to payment: in return for guaranteeing super-fast turnaround slots, the company expects to be paid in advance. For new clients, where trust might be an issue, a down-payment is acceptable, with the balance paid when the steel reaches the site. But even then, full payment must be made before the parts are unloaded.

“If we offload the steel, the ball is in their court. We’ve learnt the hard way that we just don’t get the money then,” Krajewski says.

In a dismal reflection of the prevailing attitudes in the industry, Steelo took a strategic decision to stop working with major contractors in 2011 after a leading Tier 1 contractor took six months to pay for steelwork on a high-profile bridge refurbishment. Ludicrous delaying tactics included questioning whether the parts had ever been delivered, an impossibility since the project had already been completed.

“This was not in line with our values. If we promise a delivery date and deliver, we expect the same from the other side. I only want to work with honest partners. If someone doesn’t want to work our way, there are plenty of others who will,” Krajewski says.

Only now that public opinion is pushing the industry to reform its payment practices is Krajewski willing to consider working with the larger companies again – so long as it’s on fairer terms.

“We want to work with the best of the market. And some of the new ideas we have – particularly with 3D printing – could benefit the large contractors,” he says.

Constantly on the hunt for new ideas, Krajewski experimented with artificial intelligence years before it became trendy.

“Every enquiry that comes to us has to be scanned by an estimator. We thought, why not get a computer to do it?” says Krajewski. And although the company managed to do that, it ran into problems with the sheer size of the files. “They were way too big to be used, and cloud storage was expensive at the time,” explains Krajewski.

.png)

Although that idea has been parked for now, it has given rise to other things, including ‘Mr Beam’, an online ordering platform developed in partnership with Polish software engineer Opcja, which clients can access via computer or phone.

Now Steelo is moving to the next phase, developing its 3D printing capabilities, and Krajewski cannot hide his excitement.

“Full automation is our long-term objective, and thanks to our recent 3D printing project, we are certain that it’s achievable,” he says.

Steelo is deadly serious about this and has already sponsored an MSc thesis at Cranfield University on 3D steel printing. It is continuing to explore the possibilities with research partners not only at Cranfield but also at the University of Warwick and with Foster & Partners and Lloyds Register.

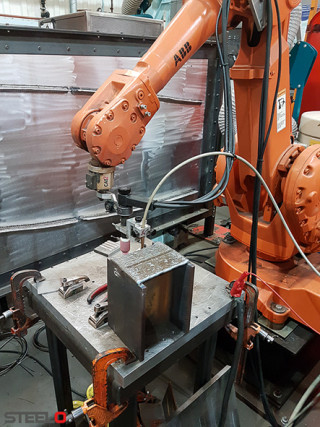

Although the group’s application for Innovate UK funding has recently been turned down, Krajewski’s response has been characteristically pragmatic. Last December, several weeks before the funding decision, he ordered a robotic welding kit. Now it has arrived, he is keen to crack on and avoid any further delays.

“Ordering the kit turned out to be a good decision. It will allow us to experiment in-house at a much faster pace. I have a feeling that the lack of funding has actually propelled our efforts, as we have to do it in a lean start-up kind of way, which is generally more successful than a fully funded venture. Humans thrive when resources are scarce,” he says.

3D steel printing: a brave new world for construction?

3D printing, or ‘additive manufacturing’, techniques for metal objects are most advanced in the aerospace industry where over the past decade research has focused on how to meet critical safety standards while reducing lead times and manufacturing costs.

Now scientists are exploring how the techniques can be adapted for other industries.

“The good news is that all the methodologies, software and hardware developed for aerospace can immediately be used for construction,” says Dr Filomeno Martina, senior lecturer in additive manufacturing at Cranfield University. “The sector can catch up quickly.”

Steelo, Cranfield University and Warwick University have teamed up with Foster & Partners and Lloyds Register to further explore the technical and commercial possibilities of 3D printing steel components.

Professor Martin Gillie, chief academic officer at the New Model in Technology & Engineering initiative, based at the University of Warwick, believes that the technique lends itself to complex geometries that would be expensive and difficult to produce through traditional welding methods.

“If we can produce more complicated shapes more easily, then we can save material,” he adds. Some estimates suggest that 3D-printed connector designs could be produced with 65% less steel compared with traditionally welded parts.

The challenge is in achieving a certification process that could cover the endless permutations of shape and design. Project partner Lloyds Register, a classification and certification body, is currently exploring how standards might be developed so that every component made of a particular material could be certified without having to go through certification every time.

Gillie predicts that 3D printing will appeal to architects who want to create nuances within a design aesthetic: “Instead of producing 10 or 100 identical connections, you might want subtle difference between them all. 3D printing offers good opportunities to do that.”

He’s also interested in exploring how to print larger structural elements, possibly combining high-strength and low-strength steels within a single component to optimise costs.

Although it is likely to be some years before robotic 3D printers are part of everyday construction kit, Krajewski’s vision is that whole steel beams could one day be 3D printed on site. In addition, Martina predicts that builders could use 3D printers to print temporary structures, such as brackets, to speed the build process.

Problem solving the Polish way

The one thing that strikes you on visiting Steelo is the large number of Poles working for the company. In fact, the production floor is entirely staffed by Poles, and there are others in the offices, along with a sprinkling of British, Greek and Czech employees.

The fact that Poles make up 60% of this small company is partly historic, according to Krajewski. He began recruiting from Polish websites when he started the company and the culture has prevailed.

But Krajewski adds that Poles are particularly attractive employees because of their broad skills base. They also have a capacity for problem solving, having grown up in a post-communist country where resources were scarce.

“If something goes wrong in the workshop, they have the right mentality to repair it themselves and get on with the work, rather than raise their hand and say someone should fix it,” he adds.

All the Poles currently employed on Steelo’s factory floor were established in the UK before they joined the company, and Krajewski believes that this helps with the stability of the workforce as younger graduates recruited directly from Poland have tended to move on too quickly.

Now that Steelo is building strong relationships with UK universities, Krajewski is hoping to offer placements to students who can help with Steelo’s research projects.

He says that he is not worried about the effects of Brexit on his workforce and although one welder has left, partly because of Brexit, most are expected to stay.

“A Polish media contact told me that the rumour that many people are moving out of the UK is not quite true. Many of the people who do leave are well connected and everyone hears about it. But we don’t hear about all the people who are still arriving,” he says.

This article was first published in the March 2019 issue of The Construction Index magazine

UK readers can have their own copy of the magazine, in real paper, posted through their letterbox each month by taking out an annual subscription for just £50 a year. Click for details.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk